One of my favorite aspects of Celtic Christianity is how the spiritual life is understood to be a journey that nobody completes in this life. While we in the US speak of belief and claiming Christ as savior and Lord – and often point to a date and time that we “were saved”, there’s more to the Christian walk than a single decision point in our lives. We are meant to continue to be formed and shaped.

The early Celtic monks expressed this understanding in how they travelled. Often a group of monks would set out to voyage and establish communities of faith where they went. Probably the most prolific of such monastery-planters was Columbanus, who travelled from his native Ireland and established monasteries in France, Germany and Italy, and was chased out of Switzerland before he could establish a monastery there.

At the core of these journeys was a mixed sense of mission, wanderlust and what the Celts described as “seeking their place of resurrection”.

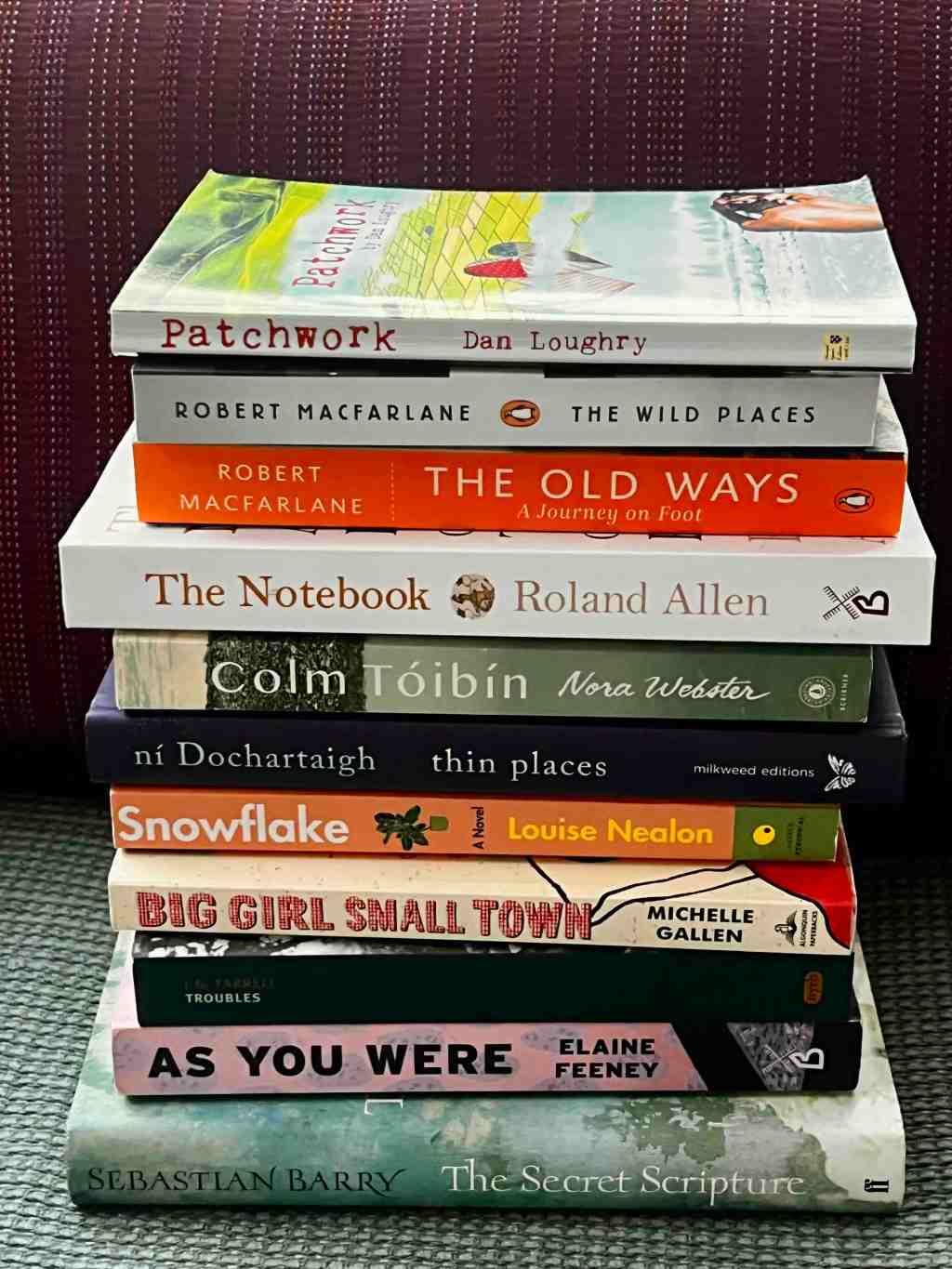

A people with a strong connection with creation, they found the presence of God within the creation that God spoke into existence, and they sensed God’s presence more in some places than others. In some places the presence of God was so tangible that they were termed “thin spaces”, where the veil between heaven and earth was so thin that it was nearly nonexistent.

Many traveling monks especially sought the place that they felt uniquely called to live and to remain – the place where their wandering would find roots. They sought their place of resurrection – that place that they planned to remain in this life, serving the people of God until their death and awaiting the great hope of resurrection. Monks found their places of resurrection in a variety of places – in Celtic lands (such as the monks who lived on Skellig Michael, pictured above) and beyond.

Some journeyed farther, as Columbanus did, gripped with a desire to find their own place of resurrection, that place where the work of God ordained for them met a physical place.

Some of these places – like Iona and Glendalough – were stunningly beautiful; others – like Skellig Michael above, were stern and required much discipline simply to survive.

These journeying monks are great examples for those of us who wander – whether physically or emotionally or spiritually. If we can step back for perspective, we can begin to see the great distinction between simply meandering with no hope and looking for our own place of resurrection.

Today, we we would label this as our call. Our call – our identity in Christ given our gifts and skills and opportunities – embeds itself in a place, and the people of that place, and the unique culture in that place. Our calls and our place will vary between us. Some of our family and friends will find our own places of resurrection to be beautiful; others will find them to be harsh and unimaginable. Our commitment to follow Christ no matter the cost takes the journey out of our own planning and puts it into his. And the presence of Christ – the thin spaces between us and the Trinity – fuels us for our mission.

May journey with Christ, and may you also find your own place of resurrection, where you choose to serve the story of Christ with joy and great hope.

See also: http://www.patloughery.com/2008/01/05/following-the-celtic-trail-day-5/

Leave a comment