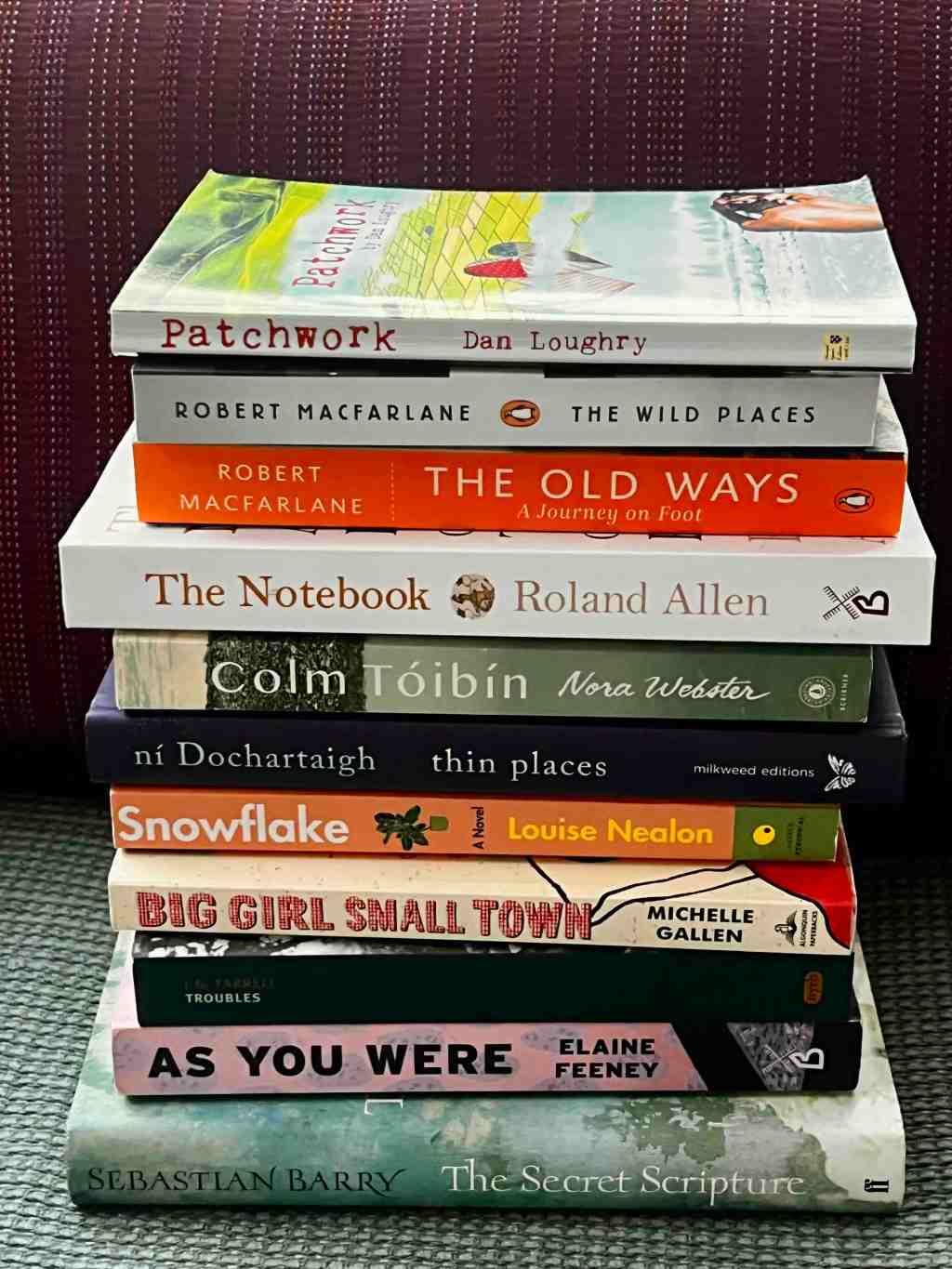

(It’s been a while since I’ve posted parts of my Celtic Trail notes. here’s Day 4 – NOW with PICTURES!. Click on the Following the Celtic Trail link down below for the previous days’ entries).

Tuesday – Day 4

On Tuesday we took a day trip to Iona. To journey to the island, our bus began with a ferry ride to the Island of Mull, then drove across Mull. From Mull we walked on to another ferry to the island of Iona.

We left at 7AM to catch the first ferry. I sat with Judi Melton on the ferry and took pictures of an abandoned castle on Mull as we approached the landing at Craignure. I also ate a Scottish breakfast, but left most of the meat on my plate.

At Craignure, we again boarded the bus for the drive across Mull. As we drove (or perhaps it was late on Monday; my journal does not note the day) we learned more about the Iona Community, which we would visit on the island.

On the trip to the island, I understood Jock to say that because some of our students hadn’t brought hiking boots as they were directed, that all of us would be doing “the short tour†of the island, as “the long tour†required sturdy boots. I was very upset by this: I wanted to experience the island as completely as possible, and I didn’t like the idea that we had to submit the entire group to some peoples’ poor planning.

I pulled Jock aside at our next stop and asked him if “the long tour†(whatever that was; I just assumed it was longer than “the short tourâ€) would be available for those of us who were prepared. I had worn my hiking boots for the entire trip, just for the Iona hike. Jock said that we wouldn’t have enough time; that our window of time after we met with John Bell was too short. I remained disappointed, but didn’t feel robbed as I had earlier.

I began to understand the difficulty of doing a learning group for such a broad range of people: some doctoral students intent on learning a focal point for their dissertation; others on vacation and interested mainly in the touring. On one hand, I liked this mix of perspectives. On the other, I didn’t want to feel that the experience was watered down to the simplest form so that everybody could participate.

On the way, our fellow student Deneuth spoke to us on the bus about his own pilgrimages to Iona. He told his own story of his spiritual journey, and he told us to expect a miracle, a transcendent experience, when we were there.

As we arrived on Iona, with the sky threatening a cold and windy day, we went directly to the Abbey to meet with John Bell. The scenery was astounding; the island has a rural feel but its beaches felt like out-of-the-way places that I’ve experienced in the Mexican Caribbean coast.

I sensed God’s voice in two ways: First, I heard a song lyric repeated over and over again, with the repeating theme of “Set your heart on pilgrimageâ€. And, from the Psalms, “The Lord causes the rain to fall on the just and the unjustâ€. On the first item, I had realized in my airport experience that this trip was more than a regular class for me, but was a pilgrimage. And on the second item, I had been thinking about the poor weather we were faced with, but more about the variety of reasons that people were describing for their trip to Iona: the beauty of the island, its historical significance, and many who were interested in a more New Age style spiritual experience who were interested in the power of crystals and other such items on the island. I felt the grace of God for those on pilgrimage, for whatever reason.

I wasn’t familiar with John before this trip, and it was clear that the other students who knew his music were very excited about this opportunity.

The Celtic saint Columba established the first monastery on Iona in 563. He and his disciples lived in a hutted community, originally with 12 beehive like stone huts. The Iona Abbey was built around 999 by the Benedictines who established their abbey for a thriving nunnery. It had two or three major renovations until the 16th century, as the Benedictines would have to rebuild after Viking raids. The Abbey was ruined after the Reformation. Stones from the abbey were used for local village homes, but has recently been rebuilt.

A worship center was established in 1890 with an emphasis on making it an ecumenical experience, which was particularly far-sighted for the time.

The Iona Community was established by George MacLeod in 1938. He initially wanted to establish a traditional seminary, but was captured by a sense of mission. They established an intentional community for both lay and ordained persons. They established a rule of life and faith that included rules for the use of time, for prayer, for meeting together, and prayer or healing of people, relationships and the land. The Community was like a Third Order of Franciscans or Benedictines, which allowed for a devoted community which was not directly a Catholic institution.

Bell spoke about the Book of Kells, the beautifully decorated Gospels which were done on Iona. Some of the imagery is North African, and some of the decorative flowers are not British. The blue dye used in the Book appears to have come from Afghanistan, and there were trade routes which would have made this possible.

Bell described the role of women in the Celtic church. There were married priests far longer than in the Roman church. Women and men learned together. And as one example, Hilda, an abbess of one of the largest communities, was responsible for educating bishops in her community.

The topic of hospitality came up. John described hospitality as not meaning “coffee and a dry old biscuitâ€, but establishing a sense that when people go to a place, they feel that they BELONG there.

John spoke next about the Psalms, which are powerfully important in Celtic spirituality. The notes that the psalmists, even in anger, never ask for vengeance for themselves, but take to the Lord their own desire to curse. He described the Psalms as “the vocabulary of spiritualityâ€, which allow all of who we are to go before all of who God is.

This emphasis on the psalms is one of the places that I most deeply connect with Celtic Christianity – and also with Hebrew spirituality. The psalms act for me as continual reminders to worship fully, and to recognize the full range of my emotions as expressible before God.

Bell talked about the lack of dualism in the Celtic tradition. Because there were no churches and no priests, lay people were all considered holy – and there was no holy and unholy separation. All could be consecrated before God. A result of this was that Celtic prayers were every earthy. We read (and prayed) prayers for kindling fires and for milking, and a wonderful prayer asking for “a great lake of beer†at the heavenly banquet.

John emphasized that any poignant moment in our life can and should be an invitation to prayer. He asked that we compose prayer for the moments that we feel most stressed about, or that we are most aware of our need the presence of God.

Next, John discussed the Celts’ understanding of incarnation as the moment in which God came so close to us that he risked death and was so intimate as to wash feet. He reminded us that in the day of Jesus, 1/3 of children died in childbirth, and ¼ of mothers died. Incarnation was risky. The idea of God’s risk to be incarnate would have helped a Celtic people who constantly lived in fear of Viking raids.

The Celts’ understanding of the incarnation was a way of making Jesus a part of the Celtic culture. I wrote this quote: “This was not the domestication of Jesus but allowing Jesus to be Lord of the culture.â€

John described three forums in which God is worshiped, each of which had unique interest to the Celtic mind.

First was the assembly around the throne of heaven, the always-eternal worship sphere.

Second is the assembled church on earth.

Third is the universe of nature which is created by God for God’s glory. We see this realm of worship in Psalm 148.

It is in this third realm that the Celts have a unique approach, and an understanding which continues to be unique today.

If the created world is meant to praise God, then the humanity who stewards it is held accountable. As John said, if choirboys were gagged and unable to praise, we would find this heinous. But if trees are gagged, why do we not also find it heinous?

When we are in nature, we often feel he presence of God. John illustrated this sensation that we have with a few stories which showed that creation doesn’t necessarily ONLY cause us to worship, but that we are present when creation itself worships, and that lifts our souls as well.

This was one of my great a-ha moments on the trip. I have always sensed the presence of God in nature in powerful ways; I love to hike and climb in the mountains near my home now as much as I did when I was a kid. But I’ve always thought that creation’s role in worship was to remind us of the glory of the Creator God, and cause us to worship. I thought that was the point of Romans 1:20, and though I still see that passage as describing Paul’s understanding of God’s glory being revealed in nature, I think the point of Creation at worship is larger. It itself worships. The mountains worship by being mountains; the trees worship by being trees.

This draws me into the realization that I worship not by singing or by praying with my friends as we gather to be the church, so much as that I worship when I am most fully Pat, the Pat I was created to be. It reminds me of Paul’s description of Jesus as ‘the second Adam’, perfectly human as much as perfectly divine. Jesus was fully and perfectly who he was intended to be; that is part of why he is an effective mediator.

I also know that “know thyself†can’t be fully prescriptive if I have no frame of reference. I only know who I am, in relationship – with my own self, but also with others who know me, and most importantly in relationship with my Creator God. It’s in this context that his love for me which fully shapes and forms me, is most spectacular. As I know and love God, and as am I am known and loved by him, as my broken parts are made whole again, I become more what I was intended to be. I more easily worship the God who heals and restores me.

I asked John to describe his understanding of Celtic monasticism in its earliest days and today. He described the focuses of prayer, work and reading/writing Scripture. When monks were sent out from Iona and other Celtic monasteries, they had memorized the Psalms and the Gospels, with a written copy of a Gospel. Perhaps they also had a written epistle or another part of the Scripture. The Psalms, however, were their spiritual language, and the Gospels were their Jesus references.

John didn’t speak much at this point about contemporary monasticism.

Another person asked for John’s thoughts on the Celtic crosses and their meaning. John spoke briefly to this frequently-asked question.

Celtic high crosses are carved from stone, and their predominant feature is the circle which surrounds the intersection of the vertical and horizontal cross members.

John suggested a few themes for the popularity of the Celtic cross: Circles represent eternity, and to the Celts, for whom time wasn’t particularly linear, the cross was eternally relevant. The circle of the cross may also have represented resurrection. And, the Celtic pagans honored the sun god, so Celtic Christians may have used the combined symbol to say that the cross supersedes the sun god. In any case, the Celtic cross is a multivalent symbol, and those who say there is a specific meaning are only guessing.

After our time with John bell, we were invited to take a walking pilgrimage tour around Iona island. By this time the sun had come out, and the first part of the path that our group of easily 50 people walked was near the water. I stayed with the group through two stops, each stop accompanied by a short exhortation about some feature of the island and a song. My impression of both wasn’t particularly positive, and I could feel my mood souring. Being on pilgrimage with a large group of tourists wasn’t my idea of pilgrimage.

I left the guided tour and went down to the water for a while, taking pictures of the stunning beach, the fishing boats, and the Caribbean blue water.

I thought for a while about typical or appropriate this was – a group began on a journey together, and I left the path to forge my own trail. I’ve done this much of my life. It felt right to me.

Further down the path, I ran into Robert, Monique and Mary, who had made it a few more stops on the path and decided to return to the village. I chatted with them but didn’t join them.

Again I left the trail and went down to the beach, taking more pictures. I pondered a seagull, wondering if it was Columba’s friend. I felt the rocks and the seaweed . I collected seashells to take back to my daughter, Kaileigh, whose seashell collection comes largely from our trips abroad and from her birth mother. I missed her greatly here, on day 4 of the trip.

I took off my boots and socks, wading out into the Irish Sea up to mid-calf, and prayed. I realized I couldn’t remember any Psalms. But I felt a connection with Columba, a true experience of his life here. It was a simple moment, and the water was cold, but it was powerful for me. I felt to grandness of God, and was knee deep in the majesty of creation.

We returned to Oban, and I had drinks with Robert, Jack and John Sr. As usual, the after-class conversation was a highlight of the day.

Leave a comment