Saturday – Day 1

I arrived in Belfast International Airport around 9:00am on Saturday. On arrival I picked up my luggage and headed for the taxi queue, first stopping at the ATM for cash. However the only cash machine in the airport wasn’t dispensing money that day, giving “Invalid PIN†error messages. I was very concerned about this – I thought I had the right PIN, and I didn’t have any pounds on me, having not exchanged dollars in favor of getting the ATM exchange rate. When another passenger behind me had the same problem, I went directly to the taxi queue – which was empty of taxis and therefore difficult to find in the Belfast International Airport. When taxis finally arrived and my turn came, I asked the taxi driver if he would take a credit card. He offered to drive me to “a hole-in-the-wallâ€, which I recalled as slang for cash machine. I took him up on the offer and also on another passenger’s offer to split the cab fare into the city.

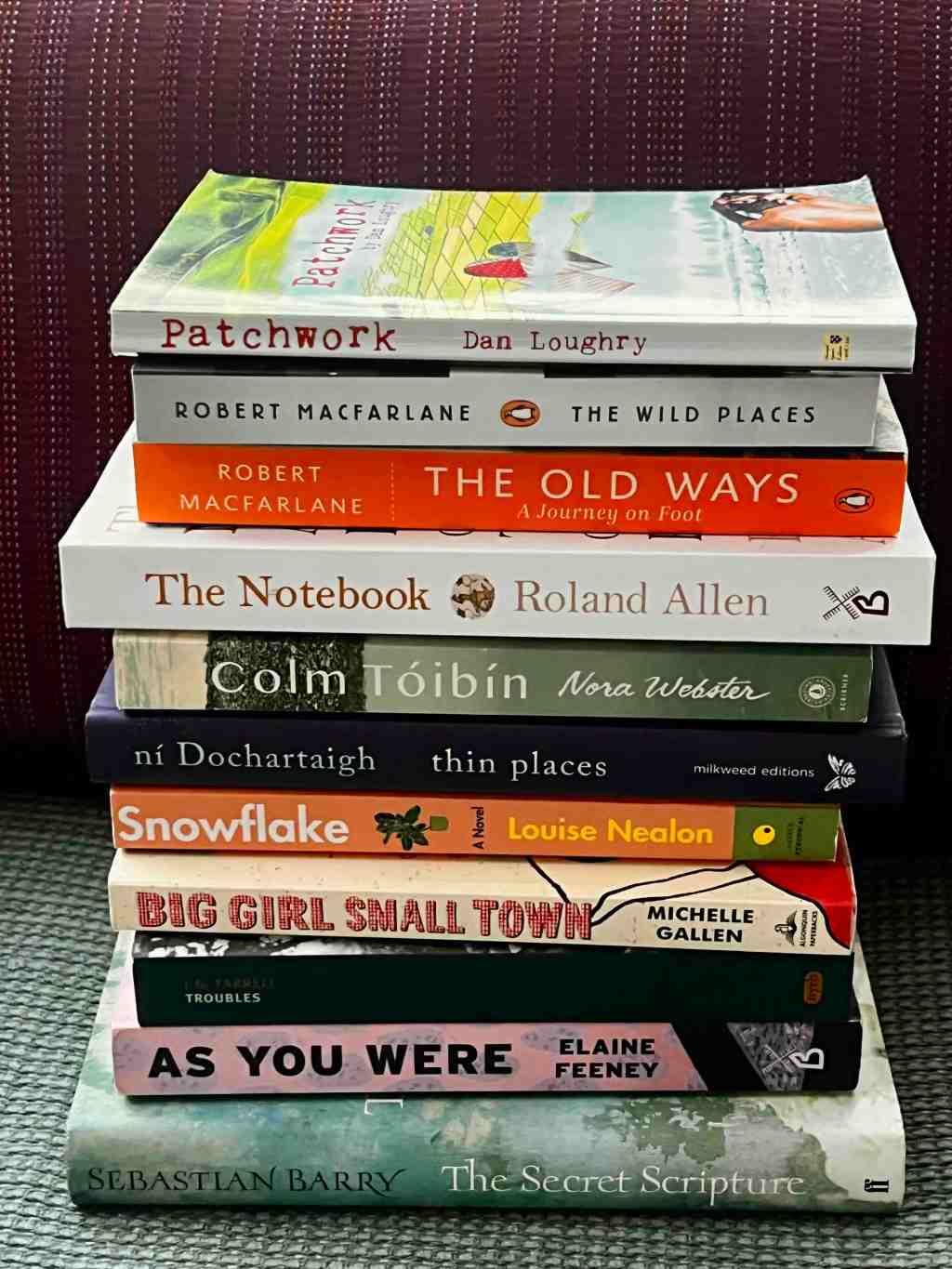

During the drive the driver did a wonderful job of acclimating me to the city and acting as tour guide, pointing out Lough Nea, the strikingly well-armored police stations and the local exercise room, and also telling me about all the mountains and lakes I must visit on my trip. On the last part of our leg he gave me his view of the Troubles, essentially saying that they were no longer a worry.

I entered the Farset International Hotel before 10am, which I knew was early. In the hotel lobby I chatted briefly with other American tourists, whom I realized later were the Lamb family, and with Mihai Pavel, and Josh Stein introduced himself to me. The lady working at the hotel desk could not check me into a room yet, but allowed me to store my bags while I went for a walk. I took my camera bag and a walking map (which I promptly ignored) and walked into the city center, taking pictures along the way of another fortified police station, some IRA graffiti on a wall, and other street art along the road. I made my way into the city and walked around the core, familiarizing myself with the center of the city and taking photos.

I walked into a shopping area which was housed inside a grand cathedral style building. In that are there was a Christian bookstore, so I wandered it out of curiosity. I was surprised to see the standard evangelical bookstore fare, with few differences in what I would expect to see at home – mostly only in the gift knick-knack area.

I was happy to find one of my favorite books, Blue Like Jazz, on sale here (as it had been in the airport in Newark, NJ). My friend Eric Sandras’ similar book, Buck Naked Faith, hadn’t made its way to either bookstore.

I was hoping to find a copy of the Bible translation that I’d seen at home but reluctantly decided not to purchase – it was a parallel translation between the Today’s NIV and The Message. Although there were several copies of The Message, I didn’t find that particular parallel translation, which was just as well – book prices were more expensive than home, and that was true even though I mistakenly believed that the exchange rate was around 1.5 dollars per pound. Near the end of the trip I realized they were around 2 dollars per pound. I’ll order this book from Bean Books (or failing that, Amazon.com), and it will become my primary carry Bible.

I had a forgettable lunch of hamburger and fries in a little restaurant in the city center, and watched BBC News. The BBC was focusing on two news stories exclusively – first, there was a development in the case of Madeline, the little girl who disappeared in Portugal when her family was on vacation. The second story was of a new foot and mouth disease outbreak in a cattle herd in England.

After lunch it was time to return back to the Farset hotel to check in and meet the class. I took a few more photos along the return walk.

In our first meeting, we were introduced to our three hosts: Robert Calvert, Jock Stein and Jack Drennan. Robert led the Trail, a Bakke faculty member who serves as a Church of Scotland (Presbyterian) minister in a church in Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Jock Stein is a Church of Scotland minister as well and would be our host in the Scotland portion of the tour. Jack Drennan is a minister in the Church of Ireland, our host in Belfast, and pastors a church in Belfast that we would worship with on Sunday.

We also introduced ourselves to the rest of the Trail participants. Perhaps half of the attendees were Bakke Graduate University students, and the rest were there at the invitation of Robert Calvert (therefore a strong Dutch contingent).

I had met two students before – Judi Melton, who is the Bakke Graduate University registrar and who has been very helpful in answering my many questions; and Jeff Hetschel, who I had met in this spring’s New Testament Theology class in Seattle.

The rest of our class were scattered around the globe, with a predominance from America and from the Netherlands. Of the American students, three (although I thought four; I later found that Glenn Barth wasn’t a CC guy) groups served with Campus Crusade for Christ and had been on a previous Trail in Italy.

A very helpful handout made its rounds – a roster of the Bakke Graduate University students with their photos attached. This helped to put names to faces, though many of the Dutch participants weren’t on the list. I jotted down notes on the roster to help me remember some details.

We had a brief introduction to the politics of the area as Jack described what we could expect to see – flags, graffiti. He tried to explain the variety of political groups that we would encounter, but I don’t think any of the students understood his well – especially the Americans, who are used to two parties, not five, and not used to the nuanced differences that Irish politics includes especially in relationship to Irish nationhood.

Jack explained that Ireland is an emotive word, and that what it means to be Irish is a very complex thought. He said that the Irish are good at talking, but that they were good at talking over each other, past each other, in these issues.

Robert described the goals of a Trail – to learn history, to experience culture, to have a long conversation on the move. He described early Celtic monks as being “God-intoxicated peopleâ€, which we would experience in the coming week.

We had our first excellent dinner together at the Farset hotel’s restaurant, a harbinger of meals to come – each of which was tasty. Our conversations were tentative as we got to know each other. This would change through the Trail.

After dinner, we split into two groups which went on a guided tour around West Belfast and specifically around the Peace Line, a series of walls which divide Catholic and Protestant communities in the city. We walked down Springfield Road through Catholic territory, then across Falls road, and back up Shankle Road, now in Protestant territory. I was in the group led by Jack Drennan.

I had walked down Springfield Road into the city center, so I was familiar with this street – I had taken pictures of IRA graffiti along this road earlier that day. But with Jack’s discussion along the way, the social picture in Belfast became much clearer.

I had read an article in ESPN Magazine in the previous month about two basketball coaches in Belfast, one Protestant and the other Catholic, who were teaching baskeball skills to middle school aged girls and arranging for them to play each other as a reconciliation project. Having taken an Irish history class in college, I was aware of the Troubles, but I hadn’t realized that tensions were still so high until that article.

I found myself afraid to look at people, and not wanting to say something that might be offensive. However, on the Catholic streets, we didn’t interact much with people outside our group. We stopped for sightseeing along several interesting sites commemorating the Hunger Strike and saw plaques and paintings on many buildings memorizlizing the heroism of Catholic fighters in recent years.

As someone who photographs the city (urban centers and its people) wherever I am, and who has an interest in street art – graffiti, murals and other communication devices, I was impressed with the quality of many of these paintings. On one particularly detailed series of wall murals, I was amused to see eight or ten panels on political statements, with one panel dedicated to a taxi company advertisement.

Jack mentioned on Falls Road that this was the site of some unmentionable horrors, allowing that this was where at one point policemen had been killed and dragged through the streets. He was unwilling to provide any more details, and we didn’t press him.

It was an eerie feeling, seeing residential life just beyond a set of high walls, many with concertina wire on top, and to consider why these walls had been erected in the first place and why they were still there. However, in this area, I saw the art and the memorial gardens, and felt compassion and empathy for the Catholics in the neighborhood who had fought the British for home rule. I found myself agreeing with their struggle, secretly supportive. On Shankle Road, I found myself empathizing with thier position as well.

In a cold rain, we turned up the Shankle Road, marking our entry into Protestant territory. The graffiti changed – the style was similar, but the content changed from emphasizing freedom fighters to now glorifying British presence and demonizing the nationalist Catholics. Again we saw street slogans, buidlding commemoration plaques memorializing fallen heroes, and a memorial garden. On this street, we saw more churches and larger pubs, many of which were organized around supporters of particular football (soccer) clubs. The Rangers supporters club, for the club in Glasgow with the predominantly Protestant fan base (archrival of Catholic-supported Celtic), was one of the largest buildings I saw.

We had just begun to chat around the memorial garden when two young men, in their early twenties and obviously quite drunk, came quickly across the road and entered the middle of our circle before we knew what was happening. One was aggressive, asking where we came from and what we were doing there, saying that we were on a sacred site.

Jack gently offered that we were walking and talking about the location. The aggressive man pursued Jack, yelling at us that we should pay him to be our guide instead of “that c*ntâ€, and we asked him to tell us the story of that garden.

He confirmed what Jack had been telling us – it was a memorial for the people killed when a Catholic man strapped explosives to his body and blew up a fish market just down the street on a weekend day. Jack was horrified at the brutality of it, mentioning several times that his mother would normally be on this street at that time.

As the drunk man was telling us this story – with very patriotic overtones – his friend, also well past sober, began to repeat a mantra, “F*ck the past! F*ck the past!â€. Our historical tour was not impressive to him. It was difficult to extricate ourselves, and to feel safe. Jeff Hetschel was masterful in this transitioning, asking the young men for a picture with them (which they did, one of them flying middle fingers), and they were happy when we left up the street.

This little conflict was a microcosm of how I felt in this walk around the peace walls in Belfast – confused, unsafe, frustrated.

I asked Jack the standard Bakke question: where are there signs of hope in your city? Jack (who I didn’t yet realize was also a Bakke D. Min student) took a while to answer. He clearly is frustrated with the lack of penetration of the Gospel in his community. I wrote his answer in my notebook:

“Any Christian who will come and live as Christians in the city, that will make a difference. That is my only hope. Otherwise…â€

Jeff, Danny, Eric and I went into a pub near the hotel on our return and processed our experience. John Lamb joined us after our first beer for a second.

On the way out the door, I spoke with an older gentleman that I’d had a brief conversation with on entering. He asked what we were in town for, and I told him we were a group of students studying Celtic Christianity. He was happy with that, and asked off-hand if I we were protestant ministers. I replied quickly, without considering the depth of the question, that we were – and as I spoke, I realized that I may be saying something that would put us at risk. I backpedaled quickly, saying that most of us were Protestants, some were Catholic (which I realized later wasn’t true), and we had an Eastern Orthodox minister, and I myself was a software engineer.

His friend, quiet for this conversation, must have noticed my unease. “It doesn’t matter,†he said. “It doesn’t matter. Enjoy Belfast.â€

We took a taxi home instead of walking the mile back to the hotel.

Of the entire Trail, the day in Belfast, and the walk around the peace wall, was the hardest for me to integrate. There are many reasons that this is true. Firstly, it had no observable connection with the early Celtic spirituality which was our focus for much of the reading, and for the rest of the trip. Most of us didn’t understand the political situation, and the explanations of unionists, nationalists, catholics, protestants, republicans, working class, suburbanites and others didn’t make sense to many of us.

However, as I now sit in the Glasgow airport waiting for my flight home, I realize that this time was invaluable because it provided no answers. One of the students said he was very frustrated by the Belfast walk because he couldn’t understand the politics, which meant that he couldn’t decide what “the answer to the problem†was. The way he said this communicated to me that he believed the situation was easily categorized, and an easy solution could be found, if only the residents of the city would follow it.

I know that no such answer exists. Even if the tangible, transformative, overwhelming presence of God were to arrive in the city – on both sides of the religious-political wall – it would take a long time for reconciliation to occur. Hatred and fear are powerful things.

Leave a comment