I went for a run this morning. My running path is really phenomenal – a gravel trail alongside the middle fork of Snoqualmie River, and within four blocks at most I’m out of suburbia and in nature. Yes, I can hear I-90 on the not-too-distant distance if I choose to, but it’s amazing how I have to think about it before I realize it’s there.

On the return leg of my short route I left the path and walked down to the river’s edge and sat on the rocks, just thinking. Praying, I suppose, but in a more settled place than I usually am. A fish jumped in front of me, and I thought about how much is happening beneath the surface that I only occasionally get to see. I watched the mountain not-change, the river continue to flow, and saw small changes occur – wood drift by, rocks fall in.

One of the ways the Celtic Christians got in trouble with their Roman counterparts is through charges of pantheism – the belief that God is all things. Roman Christianity had developed in forms that emphasized the transendance of God – his otherliness. God was “out there”, to be communicated with, but perhaps not to be communed with. It wasn’t an either-or situation of course, but this appears to be a distinctive point.

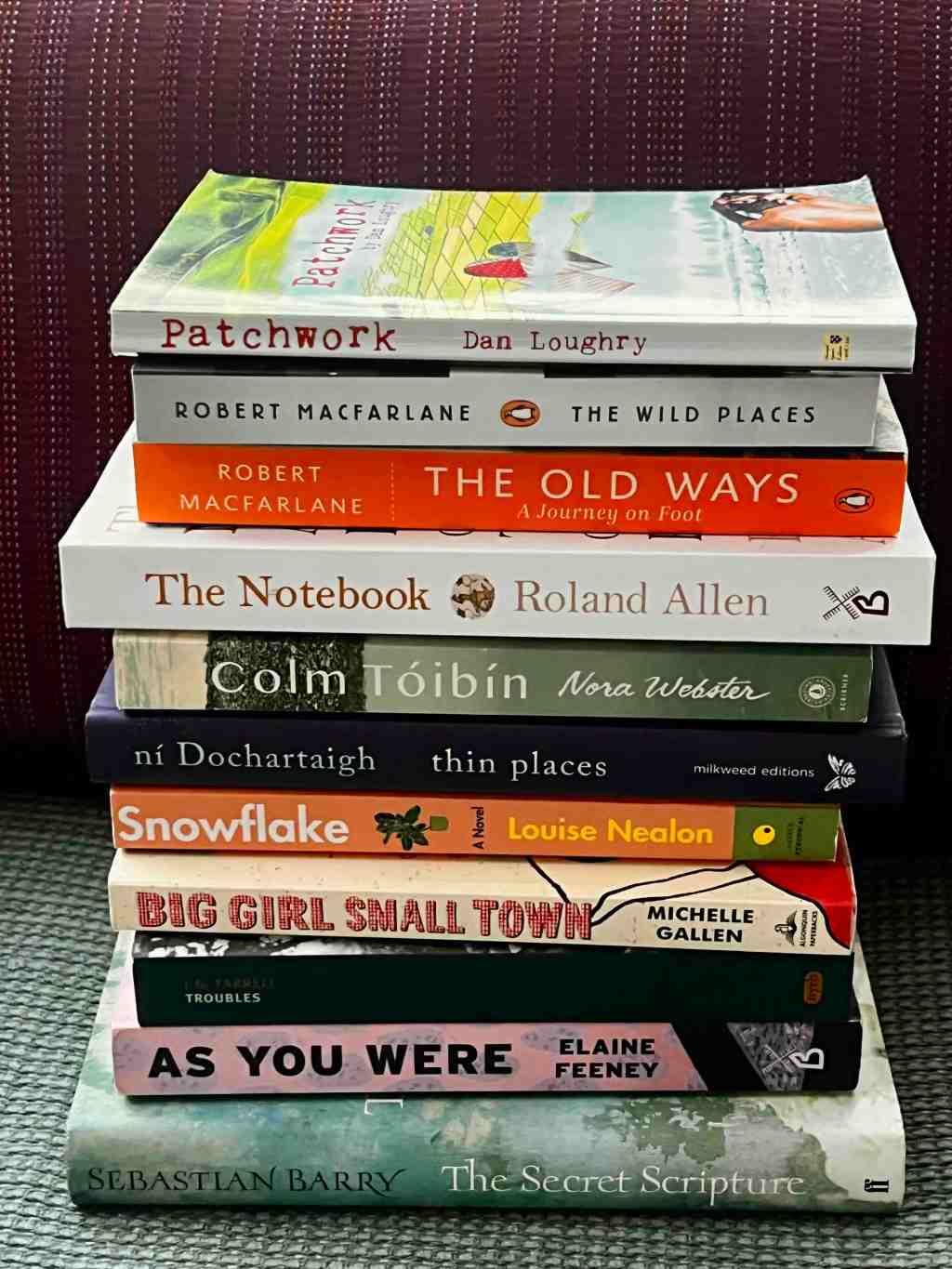

Celts were simple tribal peoples who loved nature, and so Druidic worship places were never buildings but were gathering places around rocks, trees, islands. These were places in which the presence of the divine was felt, somehow more clearly than other places. Thin spaces, where the distance between the divine and the natural seemed to be short, or not even to exist.

The Celtic Christians were more panentheists than they were pantheists – that is, they did not believe that God IS the rock and the hill and the deer; but they believed that God was a part of his creation, that he was in the creation imminently but transcended it.

Now, if you’ve read charges of pantheism against Celts, of which there are many, it would be helpful to understand the context of those sources. The great theologians and philosophers of Patrick’s day were Augustine and his followers, and they battled the alternate Christianity of Pelagius and others. Much of what I have read about Pelagius and Pelagianism is written by Augustine or his followers – and people who had theological axes to grind with the Celtic way.

As I sat at the river’s edge today I thought about the different shapes that Trinitarian spirituality can take, and how my emerging understanding of the Celtic ways has been helpful to me.

I picked up a pair of rocks to bring home to Brogan. I washed them in the river water, clutched them to me, and jogged the rest of the way home.

When I saw him, I gave him his gift. Brogan loves to bang rocks together, or to bang a rock on something hard to make noise. I told him that I knew he didn’t have many words yet, but if he wanted to use these to pray, he could: if he wanted to tell Jesus he was happy, bang the rocks together. If he wanted to tell Jesus he was upset, bang the rocks together. Let the sound of the rocks be his prayer.

Brogan smiled, and joined me in the shower, banging his rocks on the shower floor and wall. I don’t know what he prayed, but God does.

Leave a comment